There are two reasons to paddle whitewater: for the adrenaline, the thrill of riding currents and shaping form and direction out of a chaotic system, and to get to places that can only be reached on a craft moving over crashing rapids. The adrenaline paddler can ignore the views and concentrate on the technique of riding whitewater, but the destination-focused paddler can’t ignore the technical side. It’s the river that sets the cadence of where and when places can be explored. Hikers can ALWAYS stop; paddlers, not so much.

Four of us were sitting at the put-in for Overflow Creek, a steep creek in Northeast Georgia that was undergoing a renaissance of popularity in the paddling community. It was my first time down, and the people I was paddling with - my regular paddling buddy and mentor, Jack, and his friend, Ronnie - had a LOT more experience than I did. We'd met an excellent paddler by the name of Chris Harjes at the takeout while we were setting shuttle. Chris is one of those guys that has a rapid named after him on one of the hardest runs in the southeast. Although it’s named for a place where he dislocated his shoulder, you obviously still have to have serious credibility in order to injure yourself during a run, get the rapid named after you, and have that name stick. Chris joined our rag tag team and we dropped some of our cars at the take out, loaded all the boats onto a truck, and rode to the put-in.

As we were gearing up at the put-in, a beat-up little pickup pulled into the lot. Out stepped a craggy man with a long beard sporting a black eye. He started pulling out his gear which consisted of, by the standards of the day, an outdated boat, paddle, helmet, and PFD. The put-in was crowded with locals and paddlers from out of state, young guys stepping up their game, and Overflow veterans. I had paddled the area enough to know the bearded man by sight and reputation. The locals and veterans knew exactly who this hirsute paddler was, but the young virgin hotshots in their modern boats and top-of-the-line dry tops eyed him with wary suspicion. Did this guy really know what he was getting for? It was a benchmark class five creek after all. They all became silent and glanced sidelong. “What? I got a booger hangin’ out my nose or somethin’?” growled Snuffy.

Snuffy was a local Overflow/Chattooga legend, having more runs down this particular creek than the entirety of those of us gathered at the put-in. The black eye he was sporting came from a flip while running Section IV of the Chattooga the day before at a level nearing seven feet on the gauge. The normal suggested range for Section IV was from one foot to two and a half feet. My highest run was at just under three feet. Locals with many hours on the river often ran it up to about four. Seven feet was borderline deranged. On this morning, Snuffy agreed that we could paddle with him, assuming we could keep up. The normal level for running Overflow is about one foot to three feet on the local gauge. The flow on this day was just under two feet, putting it in the high-medium range. Or as Snuffy put it, "It starts to get fun at this level.” Hearing that from a man who had considered running a flood stage river the previous day fun, I felt the sudden urge to pee.

Still, by the time you are running class V rivers, there is an assumption that you should be able to take care of yourself through the easier sections of the river. I was nervous, but tried not to let it show. About two-thirds of the way down the run, Overflow is joined by two other creeks, Holcomb and Big, to form the West Fork of the Chattooga River. Unimaginatively named “Three Forks,” it is a good spot to get out and take a break before finishing the run on the larger West Fork.

“We’re just gonna Blue Angel it down to Gravity and then take a look,” Ronnie said. Gravity is considered the first substantial class V rapid on the river. The first time I heard the term “Blue Angel” regarding paddling, I automatically knew what it meant. Having grown up a Navy brat, my father had been stationed at NAS Pensacola, home of the Blue Angel Naval Aviation demonstration squadron. This group of pilots performed at air shows all over the country in their F-18A jets. Their claim to fame was their incredibly tight flight formations, wings mere feet apart and noses just out of the jet wash of the plane in front of them. In paddling jargon, this meant that we were going to go down, one right after the other, trying to stay in a close group, each paddler using the line of the person in front to line up their own approach to a rapid.

Now, one problem with Blue Angeling comes from the idea of line drift and variable paddler speed. Water pushes differently at different times, and following someone exactly is almost impossible. I was last in a group of five paddlers, so there was a high probability that my line down a rapid might bear only the vaguest resemblance to the first. I am a hand paddler, a.k.a. “a knuckle dragger,” meaning that rather than using the normal kayak paddle, I use a pair of curved plate-like paddles attached to my hands via straps. What is gained by this is an increased maneuverability, a faster roll, and, in my opinion, a more “connected” feel with the current. The tradeoff for those advantages come in the form of loss of power and speed. Considering my companions’ abilities, I would definitely be the slowest of our group on the river. Chris would try to keep up with Snuffy, Ronnie would try to keep up with Chris, Jack would try to keep up with Ronnie, and I would try to keep up with Jack.

My own water reading skills kept me in good stead through rapids with names like Hemlock Falls, Seven Car Pile Up, and Pee Wee (named ironically, I suppose). All the while I was flabbergasted at the aesthetics of the river. That is, when I was able to move my vision from the water ahead of me. The water quality, the intimate interaction with an area only paddlers get to see up close, and the light shining through hemlocks and rhododendrons forming patterns on piles of foaming whitewater and crystalizing in caustics on the river bottom kept slowing me down. I wanted to stop at every eddy and breathe it in. But, to keep Jack in sight, I had to move through the water as quickly as I could, blurring the scenery into an impression of whitewater, green foliage, grey stone, blue sky, and golden sunlight. And that’s the second problem with Blue Angeling - I wasn’t going to get to see anything! What’s the point of diving down into a roadless area full of waterfalls, near-pristine wilderness, and potential wildlife if I was going to be moving by it in a blur?

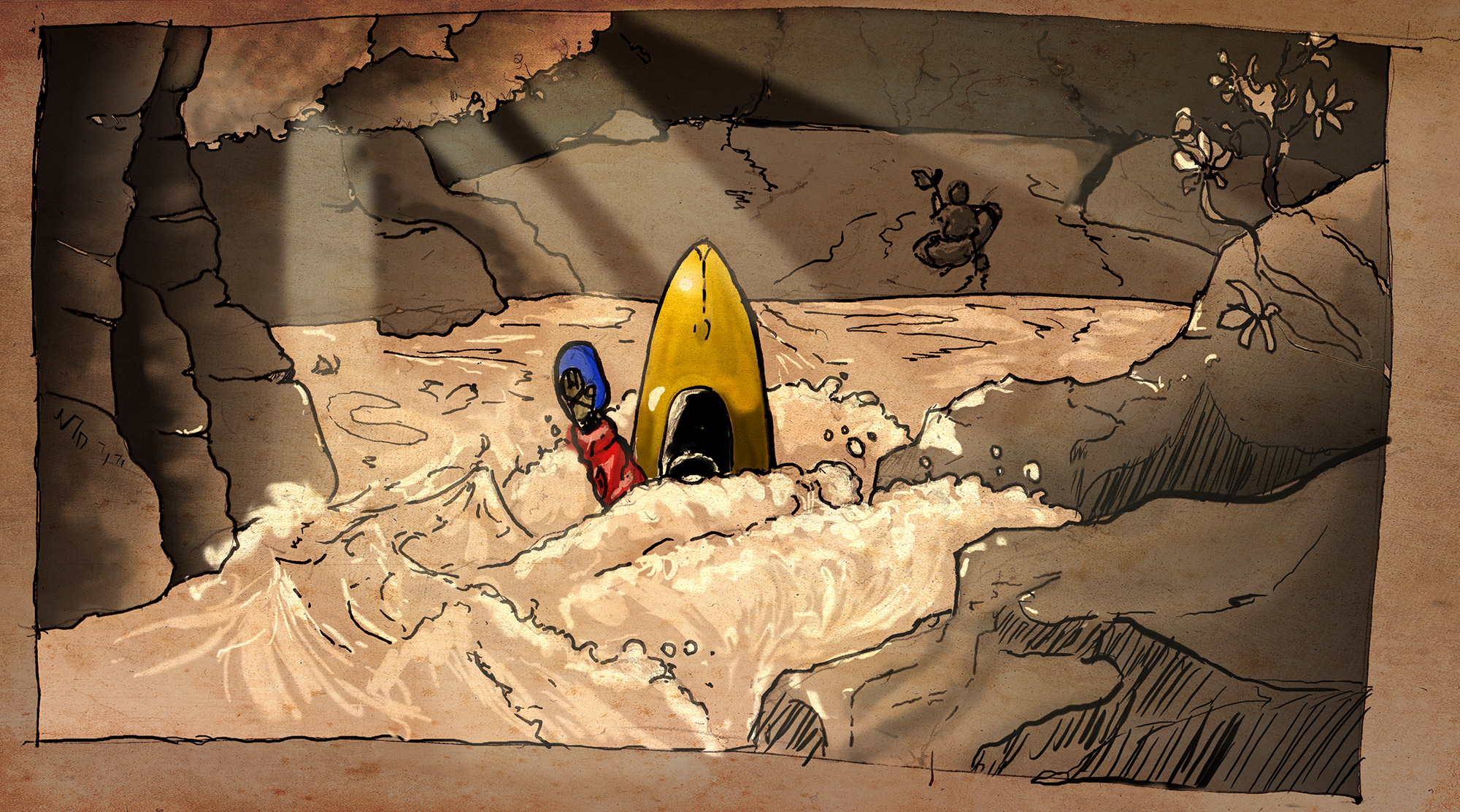

It was halfway through a rapid called Roundabout that I finally got a slightly extended view of the area. My bow got pushed slightly to the right by a wave that put me in line with a rather substantial hole that backendered me. In paddling parlance, a backender occurs when your forward momentum is slowed in relation to the current around you, causing the water to push down on the stern of the kayak, lifting the front end of the boat out of the water into a back summersault.

The view you get when backendering on Overflow is an unusual one. Your viewpoint starts at the horizon, but is quickly lifted upward, giving views of the rhododendrons along the river banks, followed by cliff faces and rock formations of crystalline schists and gneiss further up the banks of the gorge, then tall trees, mostly hemlocks, finally framing a sky that will give you a good, if short, forecast of upcoming weather. I remember focusing on one rhododendron leaf casting a shadow on the river - smoothed stone just as a beam of light passed through the spray, dragging out lines of light and dark between the leaf and its shadow’s resting place. I remember the veins on the backside of the leaf standing out clearly in a complex pattern.

"My God! This place is spectacu-” I’m sure my following words were audible only to the brook trout for which the creek was known. After a short ride in the hole, I rolled up and immediately thought about catching Jack. I rushed ahead just in time to recognize the entrance to Blind Falls, an 18 foot drop that by tradition is run without scouting it first. I ran the rapid cleanly down the center right and met the rest of my group above Gravity.

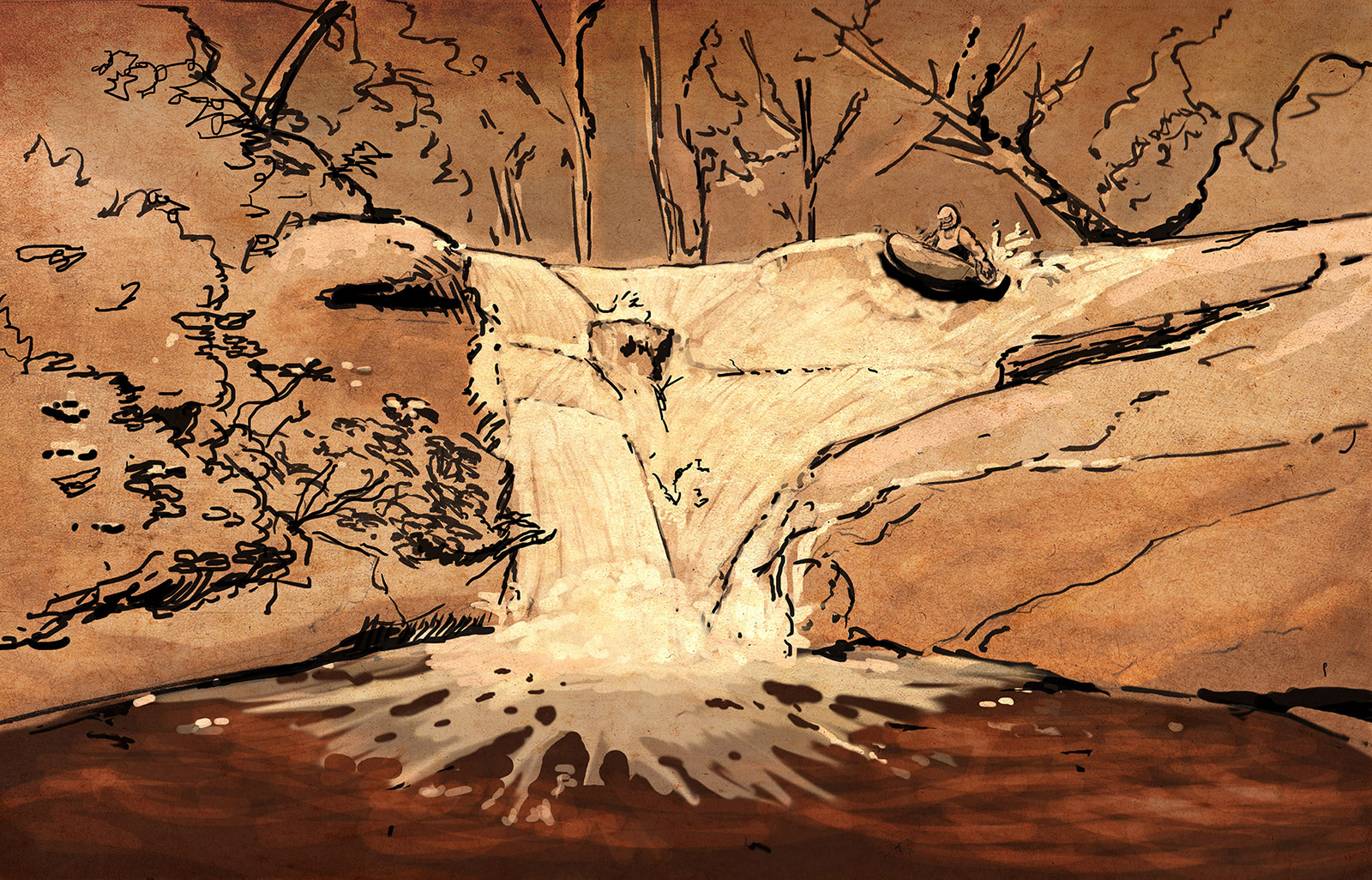

From here the difficulty stepped up a notch, and we proceeded as a group through class V Gravity, a two tiered bouncy drop, and Singley’s Falls, a sliding 30-foot high plummet into a deep pool. We had a bit more time to look around, but as with many paddlers, there was the notion of running laps - that is, finish the run and do it again to maximize the thrill of running rapids. But I simply wanted to stop and take it all in.

We reached Three Forks and I almost told the other paddlers to go on without me. It had a sublime beauty that generally appears in tourism guides - a place that, if it were more easily accessible, would appear in advertisements for the State of Georgia. But that would leave me at the top of the hardest, most dangerous rapid with no guide, so I swallowed my disappointment and moved on through the rapid Igor, which lead into the infamous Marginal Monster, a rapid with a reputation for chewing up boaters at three points through its convoluted length. I took the dry line on the left after I watched two boaters, whose skills far surpassed my own, go for extended rides in the top and bottom holes, respectively. “Dry line” means I heaved my kayak and sodden gear onto my shoulder and walked around the rapid. The rest of the run was made in a haze of spectacular scenery and pumping adrenaline. At the take out, while everyone else was planning a trip down the Toxaway River the next day, a river that the sane part of me knew I had no business paddling, for once I listened and didn’t make plans to join them. Instead, I vowed to hike into the area and take my time exploring.

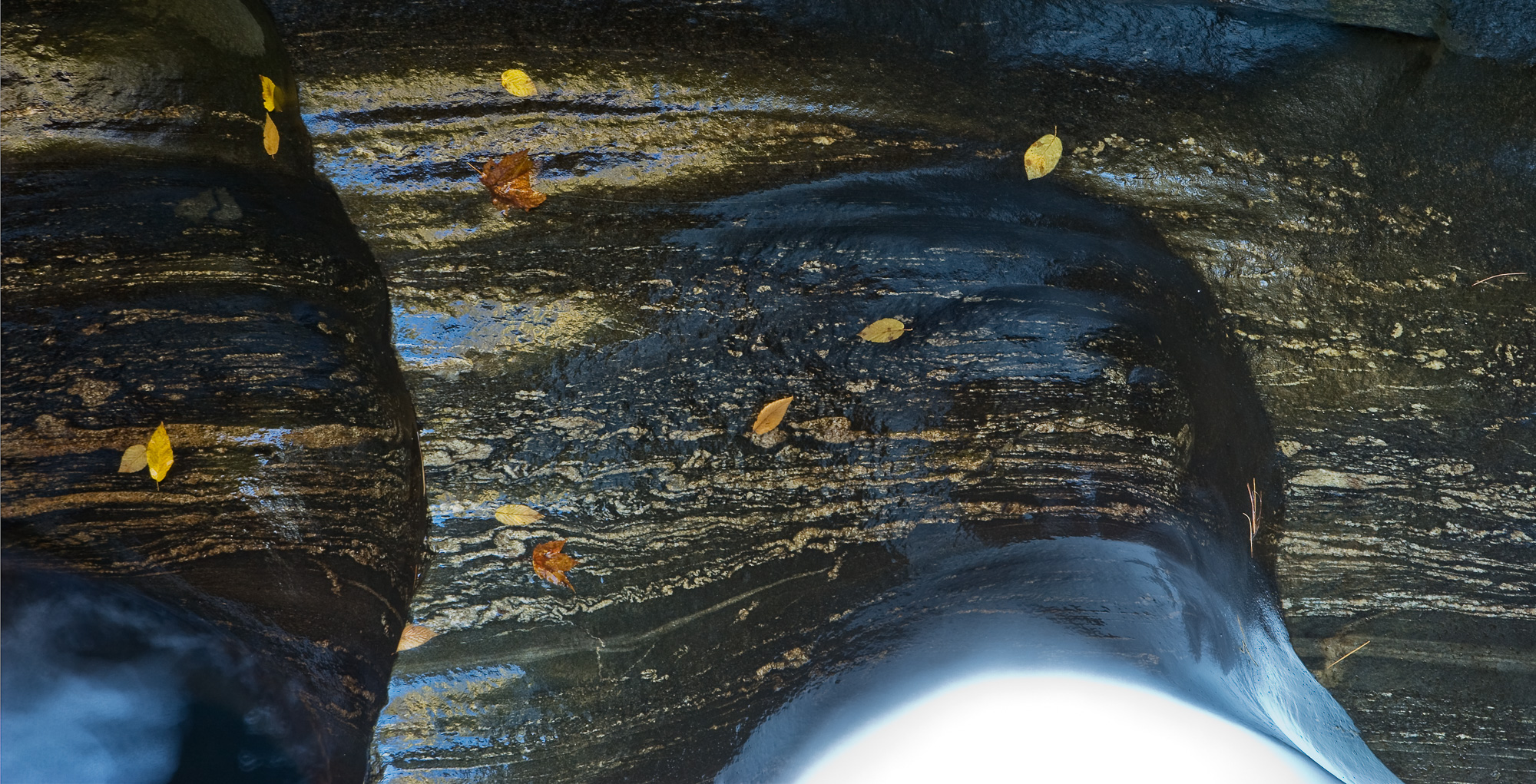

As it happened, it would be months before I had the opportunity to walk into Three Forks, the most readily accessible part of what is now the the Overflow Creek Wilderness Study Area. This area has rested in bureaucratic limbo since 1984, awaiting Congressional approval to become a fully federally designated wilderness. Brightly colored leaves covered the ground as I hiked down toward the confluence from Teague Gap, a saddle that lies along a gravel Forest Service road that cuts through the proposed wilderness. I descended down a series of trails and old logging roads that the forest had started to reclaim. Where the slope flattened out, I entered onto the slab rock banks of Holcomb Creek. Here the creek narrows down and drops through a tight gorge. Autumn leaves were plastered to reticulated stone walls like notes on a bar, the water underlining the rock in frothing white.

I crossed the creek and descended to Three Forks and set up my tent. The boom of rushing water crashing in the recesses of the stone that made up the riverbed filled my ears. I went from place to place, setting up the tripod and taking random photographs.

It was stunning, with potential for places to sit and listen to the towees and the juncos, but there was an itch, a mild discontent. All the time the white noise of the river acted as canvas for my imagination. The more I listened, the more the sounds of the river came to dominate. Suddenly, all I wanted was to feel the Wile-E-Coyote split second when I paddled off the edge of a waterfall, the moment before gravity realized I was trying to cheat her. “Hmm, I might have a focus problem here...” The balance between fast and slow, contemplation and reckless abandon. I’ve got five senses demanding attention and a brain that refuses to prioritize. “Living in the moment” and “celebrating the now” had always seemed trite phrases to me, but in theory, I had always subscribed to the concept. It’s all very zen, isn’t it?

The thing is that “in the moment” is much easier when your heart is beating like crazy. Adrenaline puts bright red marker lines under the experiences of your life. The reason I remembered my backender flip so distinctly was that there was a rather acute, “Oh shit!” moment. “Rocks!” my mind screamed, as I tensed muscles preparing for impact. “Water!” it yelped, as I instinctively held my breath. “Trees!” as I prepared to extricate myself from any entanglement I might have with branches that could catch me and hold me below water like a net. It’s a moment that gets etched in memory with all the subtlety of a sculpture made with a jackhammer. However, if our nervous systems aren’t in fight or flight mode, it takes conscious effort to convince your brain that something is worth its attention.

I returned to the part of Holcomb Creek that had drawn my interest initially. Aesthetics often fly in under the conscious radar. I stopped and looked carefully around. What had drawn me to this spot? I moved around the small canyon and let the scene slowly sink in. It was through repetition and concentration, like laying down a fine line on paper and then going over it again and again, that I saw color and texture come together slowly as I composed a scene in my mind. I anticipated the final memory; whether or not it was transferred to a physical medium didn’t seem important. I realized then that my heart was beating just a bit faster...